Chapter 1: Introduction to Psychoactive Drugs

2nd edition as of August 2022

Chapter Overview

For this first chapter, you will be introduced to psychoactive drugs: what they are, how they are used and misused, how they are classified, how drug laws have changed, and what modern drug development looks like.

Chapter Outline

1.1. Psychoactive Drugs: Use and Misuse

- 1.1.1. Drug Nomenclature

- 1.1.2. Drug Use, Misuse, Dependence, and Addiction

- 1.1.3. Determinants of the Drug Experience

1.2. Drug Laws in the United States

- 1.2.1. Drug Nomenclature

- 1.2.2. Schedule of Controlled Substances

- 1.2.3. History of Drug Laws

- 1.3.1. Drug Development Process

- 1.3.2. Patent Rights and Generic Drugs

Chapter Learning Outcomes

- Define drug and distinguish types of nomenclature.

- Contrast drug use, misuse, dependence, and addiction.

- Outline drug laws in the United States.

- Describe the process of how drugs are developed.

1.1. Psychoactive Drugs: Use and Misuse

Section Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between therapeutic and recreational use of drugs.

- Distinguish among chemical, generic, and brand names for drugs.

- Explain the differences between drug use and drug misuse.

- Describe drug dependence and drug addiction.

- Explain pharmacological and non-pharmacological determinants of the drug experience.

First, we need to define what we mean when we use the word “drug”. A drug is a chemical substance (excluding food) that can influence physiological function to restore, maintain, or enhance physical or mental health. The study of drugs and their actions and effects on living systems is called pharmacology. Pharmacology is one of the six basic sciences that contribute to medicine, veterinary medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, and other allied health sciences. The other basic sciences are biochemistry, anatomy, physiology, pathology, and microbiology. All health professional programs include these same six basic sciences but to varying degrees based on the discipline.

As this is a psychology course, we are primarily interested in drugs that can bring about changes in behavior. These drugs are known as psychoactive drugs, and the study of how they affect behavior is a subdiscipline of pharmacology called psychopharmacology.

Psychopharmacology is the interface between psychology, neuroscience, and pharmacology. To understand how drugs influence behavior, one must first understand how drugs influence the brain. To better understand how drugs influence the brain, one must understand how the brain functions. Consequently, there will be a strong orientation towards neuroscience in this OER.

1.1.1. Drug Nomenclature

Drugs can be used in two major ways, therapeutically and recreationally. Therapeutic use is the administration of a medication to treat a physical or mental ailment. In contrast, recreational use is the taking of a drug solely to enjoy or experience its pharmacological effects. Street names generally refer to recreational drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and ecstasy.

You might not have noticed, but we often refer to a drug by multiple names. We can say that we need ibuprofen or Advil®. Users might refer to cocaine as coke or methamphetamine as speed. You may have no idea what 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) is, even if you have heard of ecstasy before.

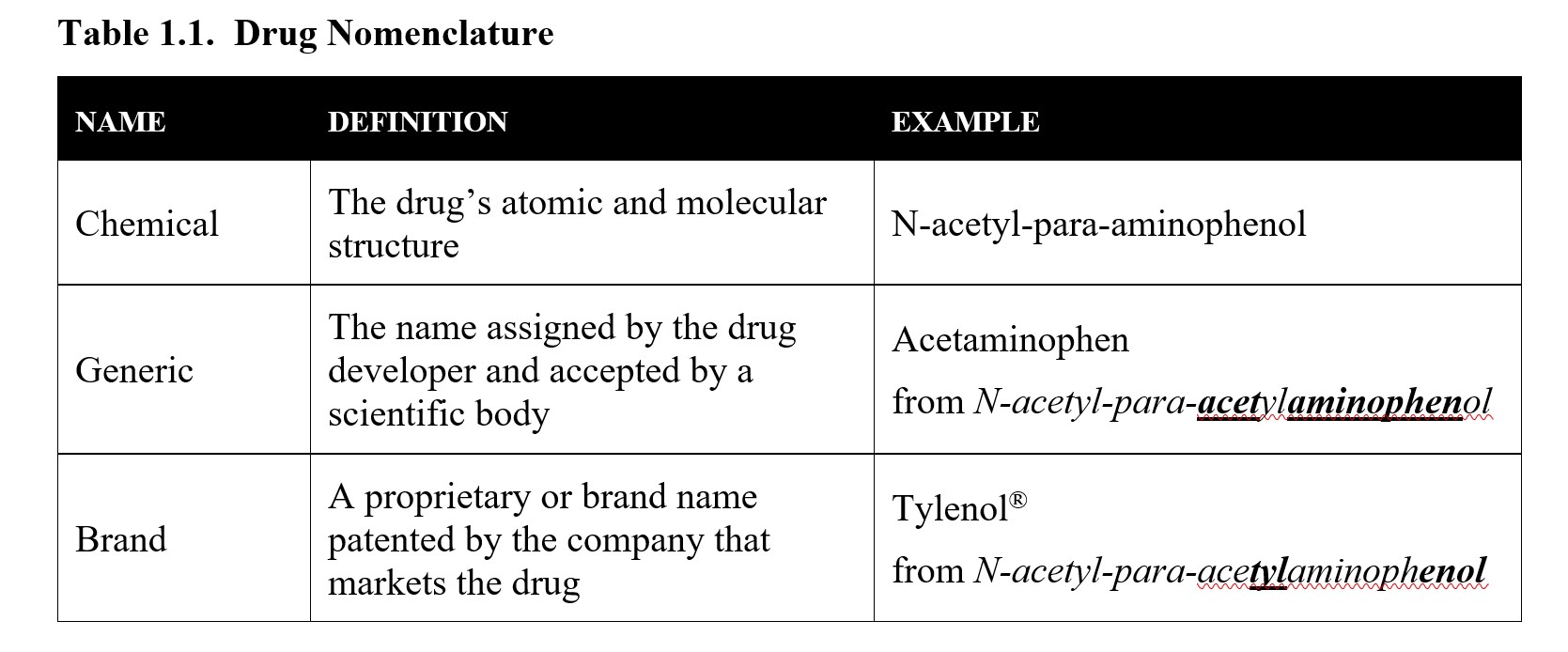

Most therapeutic drugs have generic names with one or more brand names. A generic name is a name created by the drug developer and accepted by a scientific body that indicates the drug’s classification. In the United States, generic names are approved by the U.S. Adopted Name (USAN) Council. While generic names can be used to refer to any number of chemical compounds, a proprietary or brand name is registered by the manufacturer as a trademark and refers specifically to their drug product. Proprietary names are used by drug companies in the promotion and sale of their drug. Advil® and Motrin® are different brand names used by different pharmaceutical manufacturers, but both names contain the same chemical substance known by its generic name ibuprofen. The ® symbol refers to a registered trademark.

Another way of referring to drugs is by their chemical name, which refers to the molecular structure of the drug. These names are defined by standards set by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and can end up being quite the mouthful! Take the IUPAC chemical name for ibuprofen: (RS)-2-(4-(2-methylpropyl)phenyl)propanoic acid. It is much easier to refer to it as ibuprofen. But some generic and proprietary names are derived from the drug’s chemical name. An excellent example is acetaminophen (Tylenol®) as shown below:

The process for selecting generic and brand names is a long and involved one. For the time being, you just need to be able to know the difference between the three types of names listed above. If you are interested in the process, consider reading this article from Popular Science:

FYI: How Does A Drug Get Its Name?

1.1.2. Drug Use, Misuse, Dependence, and Addiction

Earlier we made a distinction between therapeutic use of a drug and recreational use. Another way of classifying drug use is by distinguishing use from misuse. In this context, drug use means taking a drug properly in its correct dosage. Drug use does not give rise to health or behavioral problems that can harm the user or the people around them. Most people have used drugs this way such as by taking an aspirin to relieve a headache or drinking a beer.

Improper or excessive usage of a drug is drug misuse and can potentially harm the user or the people around them. Misuse can be intentional or accidental. All of the following examples constitute drug misuse:

- Injecting heroin to get high.

- Taking prescription opioids to experience relaxation instead of to relieve pain.

- Prematurely stopping a prescribed antibiotic treatment.

- Taking twice the recommended dose because the regular amount isn’t effective enough.

- Using someone else’s prescription medicine.

You may be more familiar with the term drug abuse and notice similarities between this and drug misuse. Despite that, the terms are used to refer to different things.

Drug Misuse vs. Drug Abuse

Drug misuse and drug abuse—what’s the difference? Although definitions vary, a 2013 review found that the main difference between the two is therapeutic intent. Both involve the improper use of drugs, but misuse occurs when someone intends to treat a symptom, while abuse involves taking a drug to achieve a pleasurable sensation.

The difference might not matter though, as the term abuse is on the decline. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) does not make a distinction and prefers using misuse over abuse because the latter can be shaming and contribute to stigma (NIDA, 2020a). Likewise, the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a manual used widely by clinicians for diagnostic guidelines, removed references to substance abuse and now uses the broader term substance use disorder instead.

Some sites still differentiate between the two, so it is worth being aware of the difference. In this text, abuse will only be used in specific contexts where it is necessary to delineate intent, such as in discussing drug scheduling. Elsewhere misuse will refer to any improper drug use, regardless of intent.

What are some of the risks of drug misuse? A variety of symptoms is possible depending on the specific drug, the drug dose, the frequency of drug use, and the intent of drug use. Nausea, vomiting, and blackouts from binge drinking are examples. Other changes like increased irritability or impaired decision-making can negatively impact the people around the user. There are also risks associated with repeated use of the drug. When a person uses the same drug over and over again, drug misuse can cause physiological changes that result in drug dependence. What does dependence look like? Upon the development of drug tolerance, more and more of the drug is required to produce the same effect. The body adapts to the drug, which literally works its way into how the body functions. When the drug is no longer present, the body malfunctions, resulting in the emergence of discomforting withdrawal signs and symptoms. You will learn more about tolerance and withdrawal in later chapters.

Chronic drug abuse can also lead to drug addiction, which is the compulsive drug use that continues despite awareness of its harmful consequences. Before continuing, ask yourself: is addiction a conscious choice that people make, or is it more like a medical disorder that people suffer? How would you distinguish between the two? Once you have thought about this, please read this article on drug misuse and addiction from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)

As the article indicates, the compulsive nature of drug addiction is caused in part by how the drug changes the body. Many drugs that are classified as having a high potential for abuse are self-reinforcing, meaning that they make it more likely that you will want to take the drug over and over again. The exact mechanism will be explored explicitly in subsequent chapters. In simple terms, the drug makes the user feel good. As a result, the user seeks out the drug again in the future to repeat the pleasurable experience.

Although the phrase drug addiction is used in this text, it is worth noting that the DSM–5-TR does not refer to the disorder in this way. Instead, there is a single category called substance use disorder that contains a list of diagnostic criteria and can be diagnosed as either mild, moderate, or severe. The criteria are beyond the scope of this text, but if you are interested, you may read more about them in this article on diagnostic criteria for substance use disorder.

What is the DSM?

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). The DSM includes descriptions and diagnostic criteria for different mental disorders that guide healthcare professionals in treating patients. The first edition of the DSM appeared in 1952 and is currently in its fifth edition published in 2013. In March 2022, DSM-5-TR was published, where TR stood for “text revision”. The revised text included updated text and references, and new diagnoses (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). The DSM is widely used by mental health providers in the United States, while, outside the U.S., the equivalent reference is the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) from the World Health Organization (WHO); the ICD originated in the nineteenth century. The DSM includes ICD-11 codes that are used for insurance reimbursement. The DSM focuses on behavioral health and is mainly used by psychiatrists, while the ICD is much more comprehensive in scope and is used by all health professionals. This can lead to some differences between the two classification systems.

1.1.3. Determinants of the Drug Experience

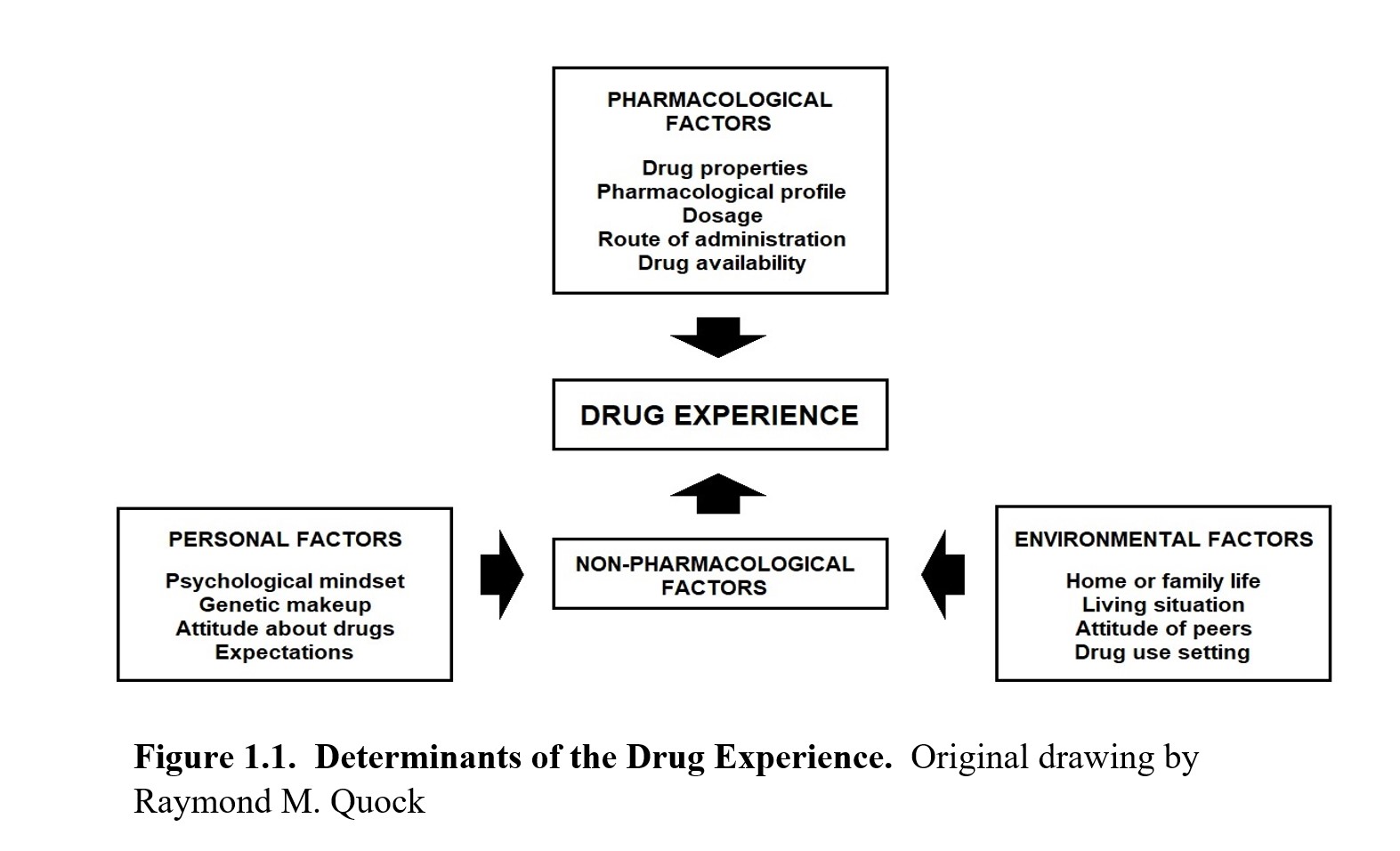

What determines whether a drug experience is positive or negative? What determines whether a drug experience is beneficial or harmful? What determines whether a single act of drug misuse turns into a full-bloomed addiction? Let us consider all the different factors that can influence a drug experience.

As you can see, multiple factors can influence the experience of taking a drug. The obvious factors involve the drug being used, and these are what we call pharmacological factors. These are the effects of the drug, its dosage, its route of administration, and any other properties that are inherent to the drug, such as price or availability. For instance, inhaling or injecting a drug is more likely to create an immediate rush of pleasure, thus increasing the chances of addiction compared to an experience with a slower onset and longer duration.

Other factors do not have to do with the drug itself, and these are the non-pharmacological factors. We can split the non-pharmacological factors into two main groups: personal and environmental factors. Personal factors are related to the person taking the drug. People’s reactions to taking drugs depend on their genetics as well as their psychological mindset at the time. Someone who is eagerly looking for an escape will perceive pleasure differently compared to someone who is already well-adjusted. These can also be tied into environmental factors, such as home or family life, peer attitudes, living situations, the drug use setting, and so on. All of these can influence a person’s response to taking a drug, which, in turn, determines whether the experience has addictive potential or not.

1.2. Drug Laws in the United States

Section Learning Objectives

- Explain the definitions of legend vs. non-legend drugs, controlled vs. non-controlled drugs, and licit vs. illicit drugs.

- Explain the DEA Schedule of Controlled Substances.

- Explain how drug laws have changed over the past century in the U.S.

Drug use in the U.S. predates even pre-colonial days. Native Americans on the east coast had many uses for tobacco, while indigenous peoples of the Southwest used hallucinogens like peyote in religious rituals. In recent times, our society has often seen drug use define entire generations. Watch this short three-minute video to get a quick overview of some of the drugs of choice in different decades:

100 Years Of Drugs In America: From Coffee To Heroin [3:17]

Throughout this long history, attempts at federal regulation have only occurred in the past century. In this section, we will look at drugs from a legal perspective. We will begin with how drugs are classified today, then review some of the historical changes that led to our current system.

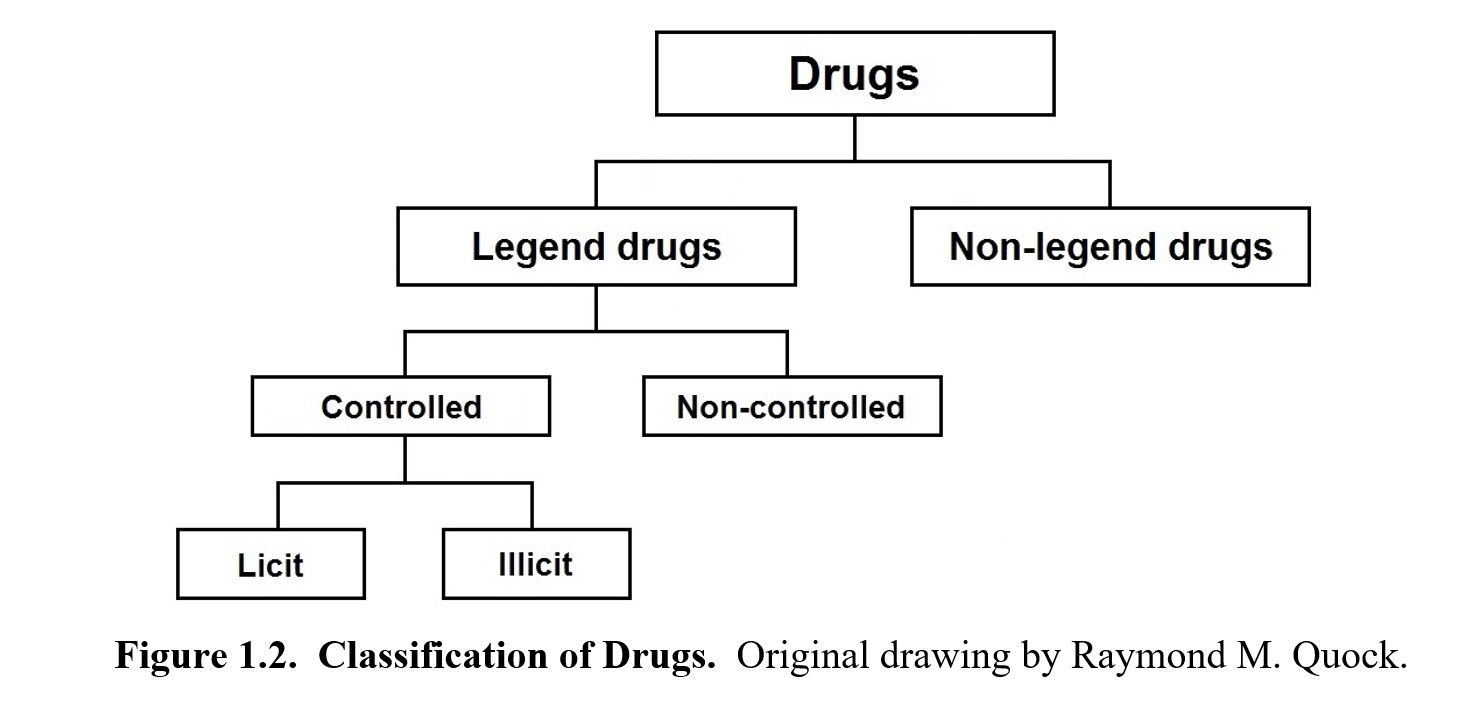

1.2.1. Legal Classification of Drugs

To explain drug laws, we will need to start by discussing how drugs are legally classified in the United States. Examine the following chart and refer back to it as you progress through this section, as it should help you keep all of these different categories straight.

The first main category of drugs is legend and non-legend drugs. A legend drug is approved for medical use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). By state or federal law, it can only be dispensed to the public with a prescription from a licensed physician or another licensed provider. The legend is a label on the drug container that usually reads “Federal law prohibits dispensing without a prescription from a licensed healthcare provider”. Because of this, they are also known as prescription drugs. To acquire these drugs, you must have a prescription filled out by a medical doctor or other licensed healthcare professional. This prescription must be presented to a pharmacist to receive the drug.

Drugs that do not belong to this first category are called non-legend drugs. As you would imagine, you do not need a prescription to purchase them. Drugs in this category are considered safe to use without the supervision of a healthcare professional, so you can simply walk into a store and buy them. As such, these are also called over-the-counter (OTC) drugs or simply non-prescription drugs. These would include your typical pain relievers, cough suppressants, and antihistamines. To compare prescription and OTC drugs, read this brief FAQ from the FDA.

Legend drugs can be further separated into controlled and non-controlled drugs. A controlled drug or substance is considered to have some potential for abuse. These drugs are subject to the Controlled Substances Act, regulated by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and categorized into five different schedules., which will be examined in the next section. Some examples are heroin, LSD, opioids, steroids, and certain sleeping pills. In comparison, non-controlled drugs are deemed to have no potential for abuse and are not regulated by the DEA. Examples include antibiotics, diabetes medications, heart medications, and asthma inhalers.

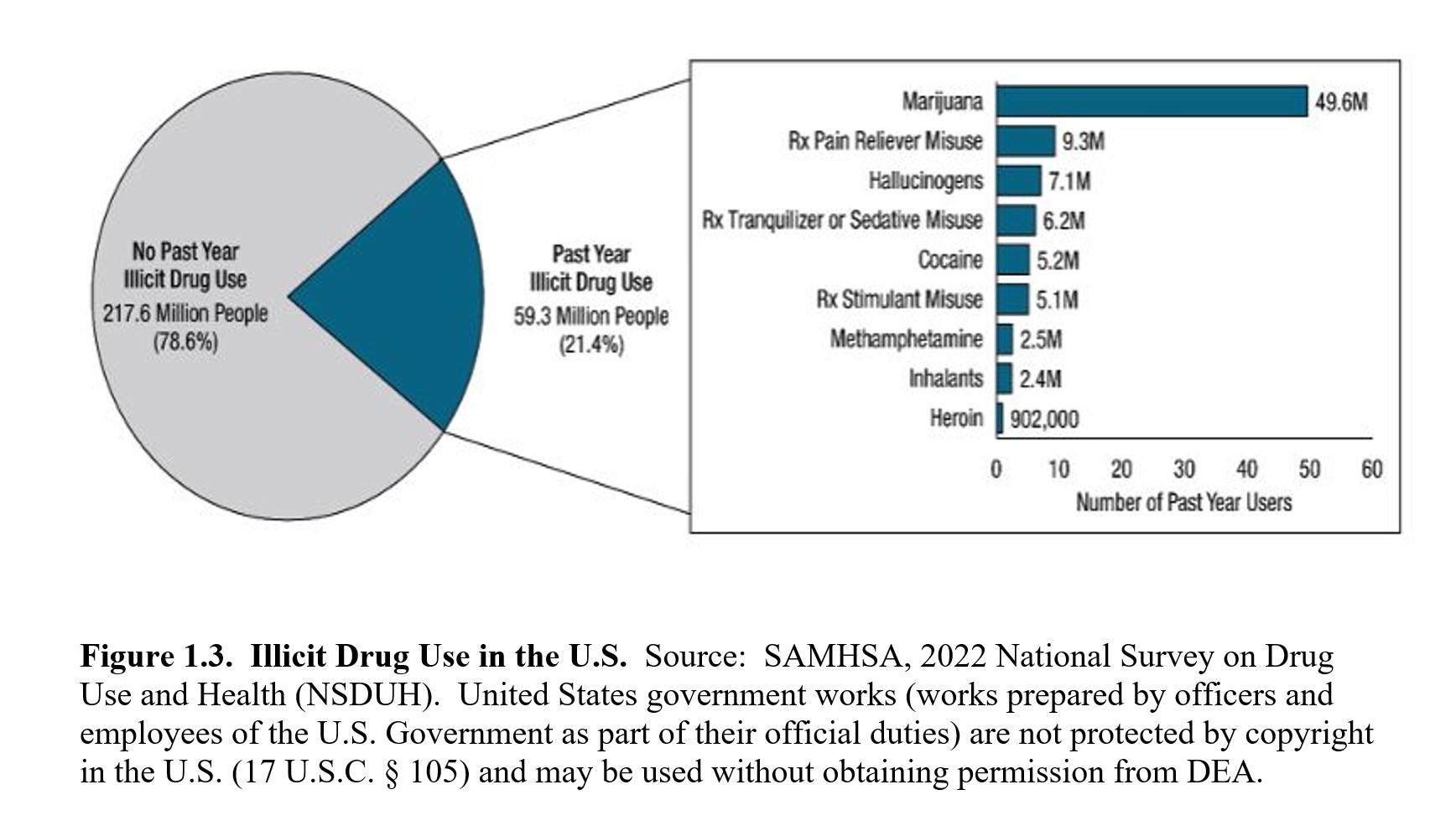

Finally, controlled substances can be either licit or illicit, both of which can be misused and abused. Licit drugs are legal drugs that have been approved by the FDA for medical use. These can include drugs that carry some abuse potential but have also been approved for specific therapeutic uses such as opioids for pain relief, psychostimulants for attention deficit yperactivity disorder (ADHD), and CNS depressants for epilepsy and anxiety. You cannot obtain these drugs without a prescription from a physician or other healthcare professional who is licensed by the DEA. On the other hand, illicit drugs are illegal drugs with a high potential for abuse but have no approved medical use. These are known as street drugs because you cannot obtain them from a pharmacy. Such drugs can include heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and many psychedelic drugs. Production, possession, and sales of such drugs are against the law and may carry stiff penalties. The following figure from the 2021 NSDUH shows the prevalence of illicit and prescription drug use in the U.S.

1.2.2. Schedule of Controlled Substances

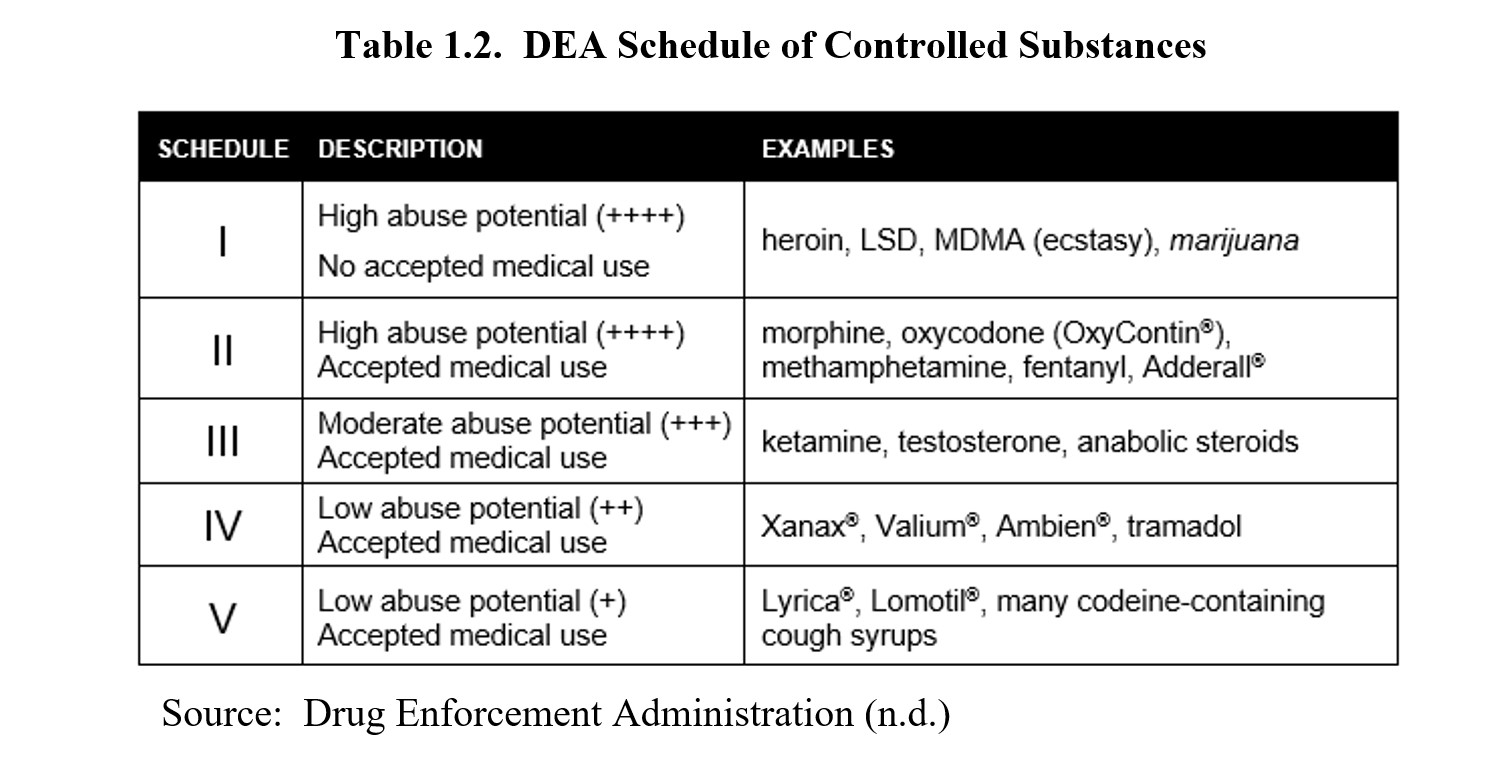

Now let us take a closer look at the drug schedules as determined by the DEA. The following table is simplified but shows the main differences between each schedule along with notable examples.

As you can see, the schedules are sorted according to abuse or dependency potential. Drugs that have a greater potential to create severe psychological or physical dependence are placed in more restrictive schedules. The most restrictive schedule is Schedule I, which also requires the substances to have no accepted medical use. Schedule II drugs also have high abuse potential but differ from Schedule I in that they have accepted medical uses. Schedules III, IV, and V drugs are all medically approved drugs but have progressively less and less abuse potential.

You may notice that marijuana is italicized. According to Federal law, marijuana is classified as a Schedule I drug, meaning it is considered to have a high risk of dependency and no accepted medical use. This is a point of contention, as evidenced by the numerous states that have legalized medical and sometimes recreational marijuana use, including Washington State. The question of whether marijuana should be legalized or rescheduled will be revisited in the chapter on cannabinoids.

1.2.3. History of U.S. Drug Laws

To understand why the DEA drug schedules were created, it is necessary to understand how drug laws have changed over the years. This section will provide a very brief overview of the major changes in U.S. drug laws—not every change will be included. If you are interested in a more in-depth look at drug legislation, the first half of this report put out by the Congressional Research Service is a comprehensive read. Doing so is entirely optional because this is a lengthy report. For this class, you will only need to know what is covered below.

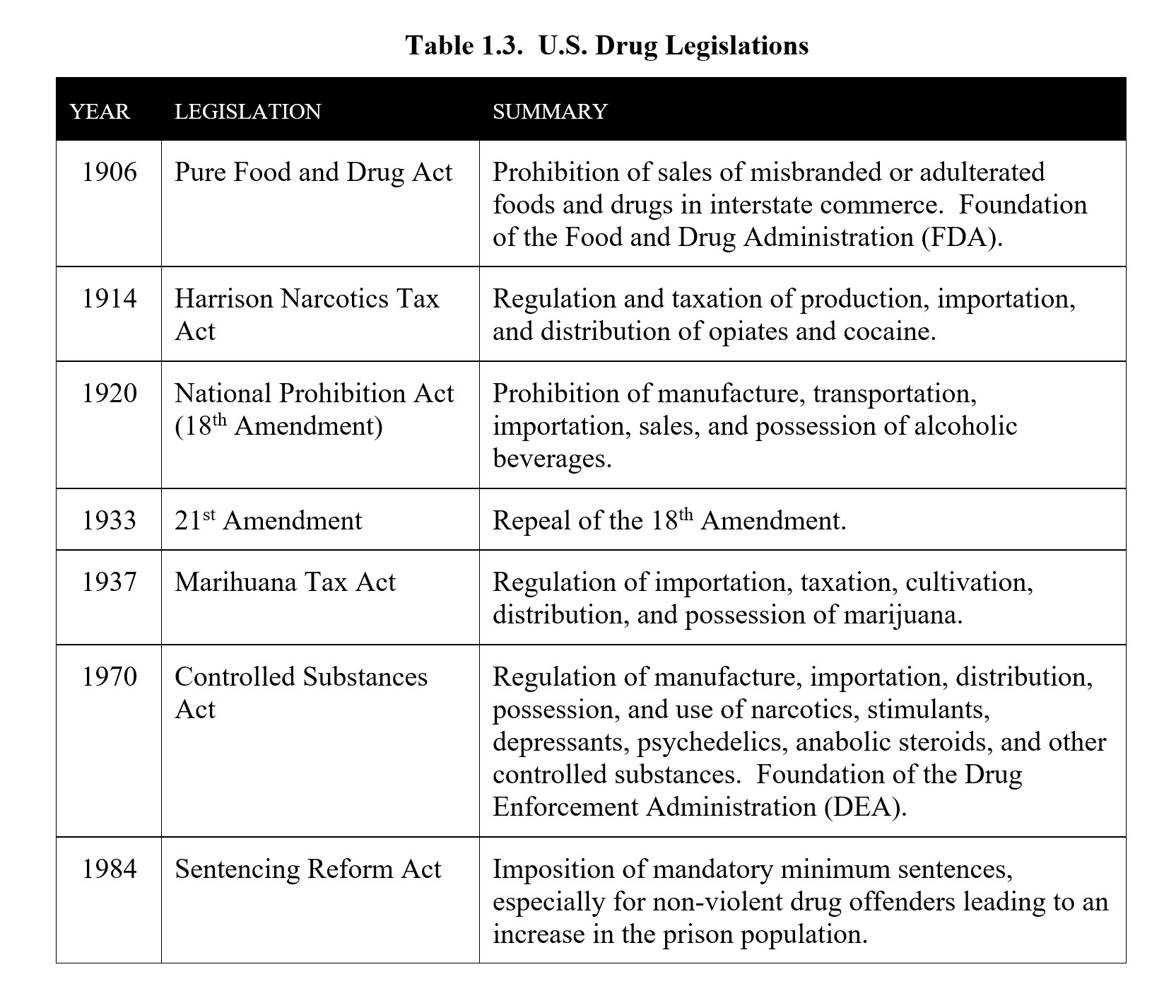

For most of U.S. history, there were no federal regulations or restrictions on the use of drugs. Drugs like opium and cocaine were freely available and used. The earliest attempts at restricting drug use were mostly at the city or state level such as the 1875 San Francisco ordinance that banned public opium dens, although not the smoking of opium itself. It was not until 1906 that the first federal legislation concerning drugs was passed. The Pure Food and Drug Act enforced labeling ingredients, regulated the contents of food and drugs, and created the Food and Drug Administration to enforce the changes. It did not place any restrictions on drug use.

The first real restrictions arrived with the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914. The Harrison Act was passed in response to growing levels of drug abuse. It required importers, manufacturers, and distributors of opium and cocaine to register with the Department of Treasury, pay taxes, and record their transactions. Physicians were still allowed to prescribe these drugs, but the interpretation of the law meant that many persons who used narcotics for non-medical purposes were prosecuted, effectively criminalizing the drugs covered under the act.

In 1920, the 18th Amendment was ratified. Also known as the National Prohibition Act or Volstead Act. It banned the manufacture, processing, transport, and sale of alcohol.

Consumption was still legal yet driven underground to speakeasies supplied by bootleggers and organized crime. There was little public support for a nationwide ban on alcohol. Prohibition was eventually repealed by the 21st Amendment in 1933.

Until 1937, the growth and use of marijuana were legal. The Marihuana Tax Act ended this by requiring a high-cost tax stamp for every sale of marijuana or hem used medically or industrially. This effectively banned the transport and possession of marijuana throughout the country. States soon made the possession of marijuana illegal after the act was passed.

In the 1960s, support for severe punishment of drug abuse started to decrease. The Presidential Commission on Narcotics and Drug Abuse of 1963 encouraged Congress to support medical approaches to treating drug dependency. At the same time, the Presidential Commission endorsed strong enforcement of drug laws which eventually led to the War on Drugs.

Perhaps the most significant change occurred in 1970 when the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) was passed. The CSA placed control of certain drugs under the federal government and was pushed by President Richard Nixon as part of his War on Drugs. The CSA essentially established total drug prohibition as the national drug policy. The CSA outlined the five schedules and later gave rise to the DEA in 1973, which still regulates controlled substances to this day. Despite recommendations to the contrary, marijuana was listed as a Schedule I controlled substance with high abuse potential and no accepted medical use.

Although the CSA has persisted for the past 50 years, drug laws have continued to change. For example, mandatory minimum sentences for drug crimes were created by the Sentencing Reform Act passed by Congress in 1984. The circumstances and history of the drug offender were not taken into account and led to a significant increase in the number and disparity of individuals incarcerated in the U.S. prison system

The changing landscape of marijuana laws is another example. While Federal law still considers marijuana to be an illegal controlled substance, many states have approved medical or recreational use of marijuana. Although it is important to understand the law as it currently stands, it is also important to recognize that the law will continue to change and adapt in response to increased research, shifts in public sentiment, and potential future health crises. The table below is a summary of the U.S. drug laws:

1.3. Modern Drug Development

Section Learning Objectives

- Explain the process of drug development, including pre-clinical trials, the different phases of clinical testing, and phase 4 surveillance.

- Explain what is meant by exclusivity in drug patent rights.

- Explain the difference in costs between originally patented drugs and generic drugs.

Earlier when discussing legend drugs, we mentioned the FDA’s New Drug Application (NDA) process. Compared to OTC medications, prescription drugs need to go through a lengthy process before being approved for marketing in the U.S. This is a consequence of the various laws that have been enacted to regulate drug contents and ensure safety and effectiveness in drugs marketed to the public. In this section, we will discuss the process for introducing a new drug to the market, as well as the laws that shape how drugs are priced and sold.

1.3.1. Drug Development Process

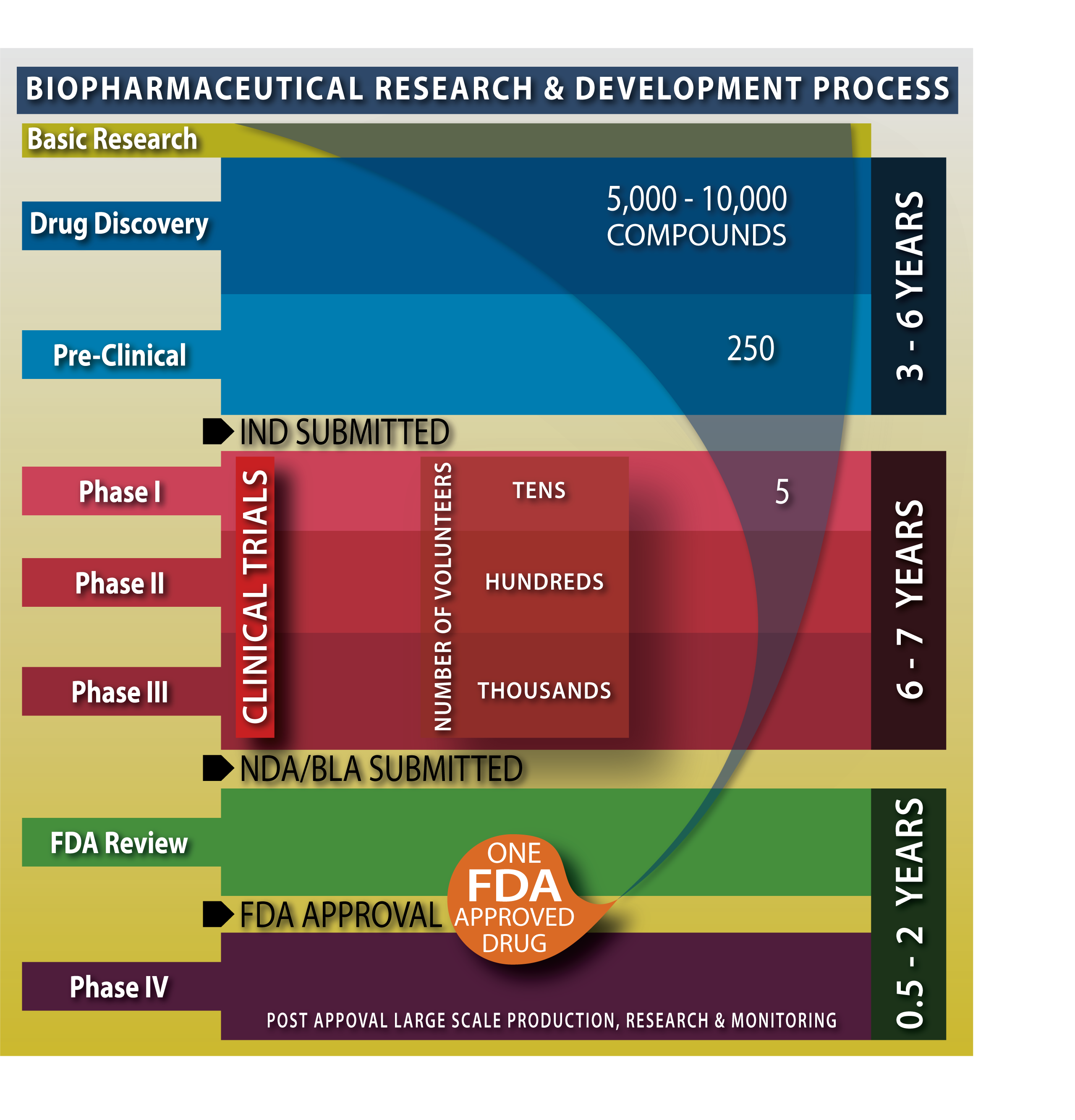

As mentioned previously, the process to develop, test, and gain approval for a new drug is a long one. How long? Consider the following graphic:

Figure 1.4. Biopharmaceutical Research and Development Process.

Original drawing by Nathan Olivier.

From drug discovery to FDA approval, the entire process can take over ten years or more. In addition, the overall success rate is very low. Numerous compounds will be synthesized and analyzed, but only a small amount will reach preclinical trials. Of those, only a handful will progress to clinical trials, and fewer still will go on to receive FDA approval. In the graph above, out of 5,000-10,000 new compounds discovered by the pharmaceutical industry, only 250 will advance to preclinical studies, and only five enter clinical trials, of which, on average, only one is approved by the FDA. What is happening at each stage that takes so long and results in so little success?

Once a compound has been identified as a potential therapeutic drug, it begins the process in the preclinical stage. Lab studies test the drug on cells, organs, and animals at this stage. Most drugs at this stage either prove to be too toxic or fail to demonstrate a sufficiently strong effect to warrant the continuation of research. Only drugs that meet strict standards for safety and efficacy are allowed to proceed to the next stage of trials. Instead of animals, human subjects are used during clinical trials. To initiate clinical trials, the company must submit an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to the FDA for its approval.

If the IND is approved, clinical trials will consist of three phases. Phase 1 emphasizes safety and determines the side effects of low doses and how the drug is metabolized and excreted in a small healthy population. Phase 2 emphasizes effectiveness instead, using a larger sample to check whether the drug has the desired effect in patients with the intended ailment. Treatment patients are compared against a control group that is provided placebos or a different drug. Phase 3 expands the sample size further and gathers additional information about how the drug performs in different populations, at different doses, and when combined with other drugs. But if at any point, a drug appears to be unsafe or not effective enough, research will cease, and the pharmaceutical company will have to start again with a new drug.

Assuming the drug makes it through all three phases of clinical trials—and only about 5% of new drugs or treatments pass all three—the New Drug Application (NDA) will finally be ready to be submitted to the FDA for approval. Even after the drug is approved and manufacturing proceeds, testing is still not over. Once a drug enters the market, it begins Phase 4 (post-marketing surveillance), where it continues to be monitored for any safety issues. If new risks are found, labeling and information will be updated, and, in rare cases, the drug may even have to be withdrawn from the market.

To review this process, check out this infographic from the FDA. Twelve steps of the drug approval process are laid out, so be sure to check it out and make sure you understand it.

How much does all this research and development cost? It is hard to pin down exact numbers. Suffice to say, the answer is “a lot.” One study from 2020 reported that the estimated research and development cost per drug averaged $985 million with a range from $314 million to $2.8 billion (Wouters et al., 2020). In addition, most drugs do not make it out of preclinical or clinical stages, and in those cases, the company sees zero return on investment. Add it all up, and pharmaceutical research is an extremely costly endeavor.

The following video from Novartis, the Swiss American multinational pharmaceutical corporation, discusses the many steps in the drug discovery and development process.

Drug Discovery and Development Process [7:21]

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) produced this short video explaining Phase 1, Phase 2, Phase 3, and Phase 4 clinical trials during the process of drug development.

What Are Clinical Trial Phases? [1:49]

1.3.2. Patent Rights and Generic Drugs

So how do pharmaceutical companies recoup this tremendous investment in research and development? For the most part, it comes from the few successes that make it through the research pipeline and go to market. To understand why a single successful new drug can be so lucrative, it is important to understand how patents work. A patent is a property right issued by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). In exchange for public disclosure of the invention, the inventor is granted the right to “exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the United States” for a limited time. This period is usually 20 years from the date the patent application was filed. During this period, the original manufacturer is the only one that can manufacture and sell the product in the U.S.

At first glance, it may seem like the pharmaceutical company would have 20 years to sell the new drug without competition. However, that is not quite the case. Companies will usually apply for a patent from the USPTO earlier on during the research and development process to stake their claim and not worry about other pharmaceutical companies beating them to the punch. So, the actual time that the company can take advantage of the patent may only be 12 years or less. This is why new drugs can be so expensive when they first come out—the company is trying to recoup all the costs of developing the drug, as well as the costs of developing the drugs that failed and did not make it out of the preclinical or clinical stages. As a result, the company has to charge a high amount over a short period to recoup its investment. For example, in 2021, the FDA controversially approved a monoclonal antibody for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. The biotech company that discovered this treatment initially announced a list price of $56,000 annually.

You may be wondering why a pharmaceutical company can’t just keep selling the drug after the patent expires. The company certainly will, but it won’t be as profitable once the patent expires. Other companies can now manufacture the same drug and sell competing versions of the drug. These versions use the generic name of the drug, not the patented brand name that the original drug was marketed under, which is why these drugs are referred to as generic versions. Generic drugs tend to be priced much cheaper than brand-name drugs, and the lower price eventually drives the price of the brand-name drugs down as well, otherwise, they won’t be able to compete. Once the patent expires, the company that developed the drug will find it much harder to turn a profit due to the increased competition.

Does that mean the obscenely high prices of drugs are justified? Perhaps not. Recent investigative journalism has pointed to a large discrepancy between spending on research and development versus marketing. An episode of Last Week Tonight with John Oliver from 2015 revealed that 9 out of 10 of the top pharmaceutical companies spent more on marketing than research. Marketing strategies include maintaining a staff of pharmaceutical sales representatives, a marketing workforce, sponsorship of continuing medical education programs and cruises, drug coupons, free drug samples, direct-to-consumer advertising, and consultant fees to physicians. While the companies disagree with the numbers, they, nevertheless, continue to pour billions of dollars into drug ads and marketing to doctors, as this 2019 article points out. This practice can create conflicts of interest in health care professionals and may be contributing to medicalization (also called disease mongering) and an increase in demand for prescription remedies.

If you are interested in watching the original piece by John Oliver on the subject, you can find it on YouTube:

Marketing to Doctors: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO) [17:12]

Chapter Recap and Practice Questions

In this chapter, we introduced the main focus of this course: psychoactive drugs. We discussed how these drugs are named, the various ways they can be used, and what factors influence the drug experience. We also covered the history of drug laws in the United States, including how to legally classify drugs and the different schedules of controlled substances. Finally, we explored the modern drug development process and how prices are influenced by patents and generic drugs.

Chapter 1 Practice Questions

Answer the following:

- What is the difference between recreational and therapeutic drug use?

- What is the main difference between a generic drug and a brand name? Provide an example of each.

- What is the difference between drug use and misuse?

- Explain drug dependence.

- What are some things that might affect whether someone has a good or bad experience with a drug? Provide an example of a pharmacological factor, a personal factor, and an environmental factor.

- What are legend drugs also called? What about non-legend drugs?

- What is the difference between licit and illicit drugs?

- How many schedules are there in the DEA’s classification of controlled substances? Define the criteria for each schedule.

- Name seven important changes in the history of drug laws in the United States. What were the key changes from each?

- How many phases of drug development are there? Name each one and describe how it is conducted.

- How long are drug patents in the United States? When does this period start?

- Explain why the costs of new medications are so high.

2nd edition